There was some interesting discussion yesterday in my Facebook feeds concerning the subject of “Liberation Theology”. Since I am deeply interested in theology, believe in liberating the poor and marginalized and wish to respond in the best possible way to the challenges I face daily as a gospel preaching, whose theological base is Reformed and Evangelical, community activist, working with homeless and other vulnerable groups, who is ambivalent when it comes to supporting political parties (in recent years I voted Conservative, Labour, Lib Dem, UKIP and Green), I was naturally interested and threw in my own two penneth worth.

I found, unsurprisingly, many write ups upon googling the subject “Liberation Theology”. This was a phenomenon I first came across as a young Christian, but was to be steered away from giving it too much credence by my “wiser” older mentors, given that they deemed it to be doctrinally unsound and, besides which, in those days the “social gospel” was deemed to be the domain of those dastardly liberals and anything tainted with Catholicism was dismissed out of hand. I am pretty sure though that for any who wanted to research this subject before coming to a view there is a load of stuff out there that will prove helpful. My first hit giving a definition: “a movement in Christian theology, developed mainly by Latin American Roman Catholics, which attempts to address the problems of poverty and social injustice as well as spiritual matters”, set me on my way.

My next pertinent hit gave more depth:

BEGIN QUOTE

“”Love for the poor must be preferential, but not exclusive” Ecclesia in America, 1999.

Liberation theology was a radical movement that grew up in South America as a response to the poverty and the ill-treatment of ordinary people. The movement was caricatured in the phrase If Jesus Christ were on Earth today, he would be a Marxist revolutionary, but it’s more accurately encapsulated in this paragraph from Leonardo and Clodovis Boff:

Q: How are we to be Christians in a world of destitution and injustice?

A: There can be only one answer: we can be followers of Jesus and true Christians only by making common cause with the poor and working out the gospel of liberation.

Liberation theology said the church should derive its legitimacy and theology by growing out of the poor. The Bible should be read and experienced from the perspective of the poor.

The church should be a movement for those who were denied their rights and plunged into such poverty that they were deprived of their full status as human beings. The poor should take the example of Jesus and use it to bring about a just society.

Some liberation theologians saw in the collegiate nature of the Trinity a model for co-operative and non-hierarchical development among humans.

Most controversially, the Liberationists said the church should act to bring about social change, and should ally itself with the working class to do so. Some radical priests became involved in politics and trade unions; others even aligned themselves with violent revolutionary movements.

A common way in which priests and nuns showed their solidarity with the poor was to move from religious houses into poverty stricken areas to share the living conditions of their flock.

END QUOTE

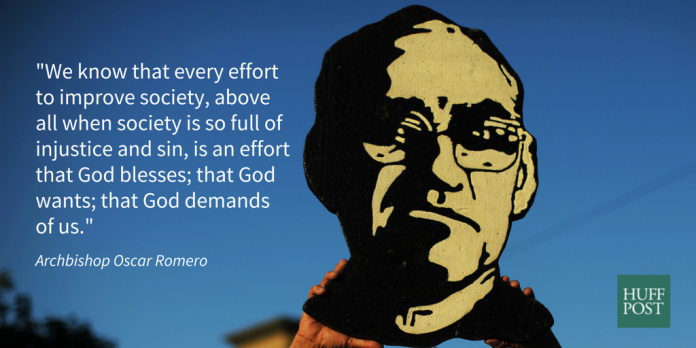

The article went on to discuss the objection of Pope John Paul II, for example: “His main object was to stop the highly politicised form of liberation theology prevalent in the 1980s, which could be seen as a fusion of Christianity and Marxism. He was particularly criticised for the firmness with which he closed institutions that taught Liberation Theology and with which he removed or rebuked the movement’s activists, such as Leonardo Boff and Gustavo Gutierrez. He believed that to turn the church into a secular political institution and to see salvation solely as the achievement of social justice was to rob faith in Jesus of its power to transform every life. The image of Jesus as a political revolutionary was inconsistent with the Bible and the Church’s teachings”. It also gave as an example, interesting for me because I see him as a role model, one of leaders in the South American church, who fought injustice and was killed because he did so: “Óscar Romero (1917-1980) … One of the most high profile clerics associated with liberation theology was the Archbishop of San Salvador, Óscar Romero. Initially considered a social conservative, he became increasingly an outspoken advocate for the poor and oppressed as the security situation in El Salvador deteriorated in the late 1970s. He was assassinated while saying mass in a cancer hospice in San Salvador on 24th March 1980”. There are so many more avenues that can be usefully explored, but I desist for the time being.

One of the reasons I didn’t get involved in my earlier days with Liberation Theology was that the key exponents at the time were Catholic and associated as I was with fundamentalist leaning circles, I was at the other end of the theological spectrum. But truth is truth, who ever says it, and I have come to a view that seeking out truth and practicing it is perhaps the most noble pursuit any of us can make. It is painful, to be sure, because it is so much easier to adopt a position to the exclusion of any other that does not recognize that position. Politically, I am neither left nor right because I do not see scriptural warrant for either view. If one were to cite Old Testament theocracy, it was more conservative leaning (small state etc.) to be sure but it only worked because people gave to the poor because they feared God. If one were to cite the New Testament church, where members had “all things in common”, they did so freely and not because an ideologically flawed state hierarchy dictated what the priorities are to be. As for religion, the book that has particularly inspired me in the past year that touches on some of the concerns of Liberation Theology, from a different angle, is Generous Justice by Tim Keller (see here). My own journey toward theologically and practically embracing the teaching I now see so clearly laid out in scripture on social justice is detailed in: “Outside the Camp”.

But this is how I see it … There have been many movements in the history of the church, and many (maybe all) have been prone to error, so discernment is needed if adherence to truth is going to be our guiding principle. While I dislike labels, I declare I am an Evangelical because I believe scripture should be put before the authority of the church and the light of reason, but without discarding either. I declare myself Reformed because those who were ascribed that label often in my view had a clearer and more correct understanding of scripture (in this current era, someone like J.I.Packer), yet someone like C.S.Lewis, who is deemed as not reformed, is still one of my theology heroes. I believe we need to study the scriptures carefully and prayerfully, relying on the guidance of the Holy Spirit, mindful of the teachings of the church and the need to apply reason. However we look at it, we are here to serve our Lord Jesus Christ, who declared at the outset of his ministry: “The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me; because the Lord hath anointed me to preach good tidings unto the meek; he hath sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to them that are bound; To proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord, and the day of vengeance of our God; to comfort all that mourn” Isaiah 61:1-2. As for us, we are called to love God and our neighbor (rich and poor) also.

Maybe you are a socialist, pacifist anarchist?